The Little Mermaidby Hans Christian Andersen |

La virineto de marode Hans Christian Andersen |

| Far out in the ocean, where the

water is as blue as the prettiest cornflower, and as

clear as crystal, it is very, very deep; so deep, indeed,

that no cable could fathom it: many church steeples,

piled one upon another, would not reach from the ground

beneath to the surface of the water above. There dwell

the Sea King and his subjects. We must not imagine that there is nothing at the bottom of the sea but bare yellow sand. No, indeed; the most singular flowers and plants grow there; the leaves and stems of which are so pliant, that the slightest agitation of the water causes them to stir as if they had life. Fishes, both large and small, glide between the branches, as birds fly among the trees here upon land. In the deepest spot of all, stands the castle of the Sea King. Its walls are built of coral, and the long, gothic windows are of the clearest amber. The roof is formed of shells, that open and close as the water flows over them. Their appearance is very beautiful, for in each lies a glittering pearl, which would be fit for the diadem of a queen. The Sea King had been a widower for many years, and his aged mother kept house for him. She was a very wise woman, and exceedingly proud of her high birth; on that account she wore twelve oysters on her tail; while others, also of high rank, were only allowed to wear six. She was, however, deserving of very great praise, especially for her care of the little sea-princesses, her grand-daughters. They were six beautiful children; but the youngest was the prettiest of them all; her skin was as clear and delicate as a rose-leaf, and her eyes as blue as the deepest sea; but, like all the others, she had no feet, and her body ended in a fish's tail. All day long they played in the great halls of the castle, or among the living flowers that grew out of the walls. The large amber windows were open, and the fish swam in, just as the swallows fly into our houses when we open the windows, excepting that the fishes swam up to the princesses, ate out of their hands, and allowed themselves to be stroked. Outside the castle there was a beautiful garden, in which grew bright red and dark blue flowers, and blossoms like flames of fire; the fruit glittered like gold, and the leaves and stems waved to and fro continually. The earth itself was the finest sand, but blue as the flame of burning sulphur. Over everything lay a peculiar blue radiance, as if it were surrounded by the air from above, through which the blue sky shone, instead of the dark depths of the sea. In calm weather the sun could be seen, looking like a purple flower, with the light streaming from the calyx. |

Malproksime en la maro

la akvo estas tiel blua, kiel la folioj de la plej bela

cejano, kaj klara, kiel la plej pura vitro, sed ghi estas

tre profunda, pli profunda, ol povas atingi ia ankro;

multaj turoj devus esti starigitaj unu sur la alia, por

atingi de la fundo ghis super la akvo. Tie loghas la

popolo de maro. Sed ne pensu, ke tie estas nuda, blanka, sabla fundo; ne, tie kreskas la plej mirindaj arboj kaj kreskajhoj, de kiuj la trunketo kaj folioj estas tiel flekseblaj kaj elastaj, ke ili che la plej malgranda fluo de la akvo sin movas, kiel vivaj estajhoj. Chiuj fishoj, malgrandaj kaj grandaj, traglitas inter la branchoj, tute tiel, kiel tie chi supre la birdoj en la aero. En la plej profunda loko staras la palaco de la regho de la maro. La muroj estas el koraloj, kaj la altaj fenestroj el la plej travidebla sukceno; la tegmento estas farita el konkoj, kiuj sin fermas kaj malfermas lau la fluo de la akvo. Tio chi estas belega vido, char en ciu konko kushas brilantaj perloj, el kiuj chiu sola jam estus efektiva beligajho en la krono de reghino. La regho de la maro perdis jam de longe sian edzinon, sed lia maljuna patrino kondukis la mastrajhon de la domo. Shi estis sagha virino, sed tre fiera je sia nobeleco, tial shi portis dekdu ostrojn sur la vosto, dum aliaj nobeloj ne devis porti pli ol ses. Cetere shi meritis chian laudon, la plej multe char shi montris la plej grandan zorgecon kaj amon por la malgrandaj reghidinoj, siaj nepinoj. Ili estis ses belegaj infanoj, sed la plej juna estis tamen la plej bela el chiuj; shia hauto estis travidebla kaj delikata, kiel folieto de rozo, shiaj okuloj – bluaj, kiel la profunda maro; sed, kiel chiuj aliaj, shi ne havis piedojn, la korpo finighis per fisha vosto. La tutan tagon ili povis ludi en la palaco, en la grandaj salonoj, kie vivaj floroj elkreskadis el la muroj. La grandaj sukcenaj fenestroj estis malfermataj, kaj tiam la fishoj ennaghadis al ili, tute kiel che ni enflugas la hirundoj, kiam ni malfermas la fenestrojn. La fishoj alnaghadis al la malgrandaj reghidinoj, manghadis el iliaj manoj kaj lasadis sin karesi. Antau la palaco sin trovis granda ghardeno kun rughaj kaj nigrabluaj floroj; la fruktoj brilis kiel oro kaj la floroj kiel fajro, dum la trunketoj kaj folioj sin movis senchese. La tero estis la plej delikata sablo, sed blua, kiel flamo de sulfuro. Super chio estis ia blua brileto. Oni povus pli diri, ke oni sin trovas alte supre, en la aero, havante nur chielon super kaj sub si, ol ke oni estas sur la fundo de la maro. En trankvila vetero oni povis vidi la sunon, kiu elrigardis kiel purpura floro, el kiu venis lumo chirkauen. |

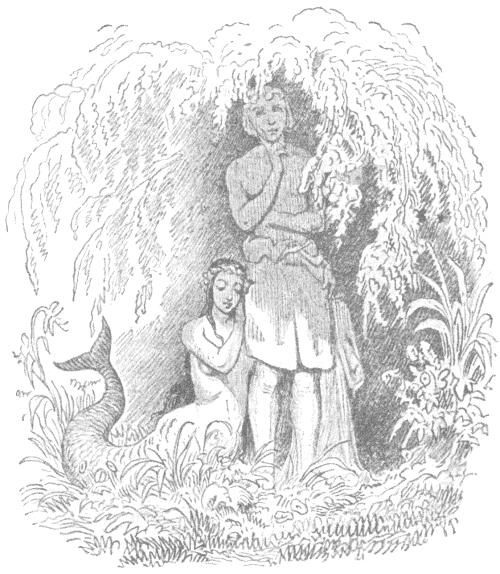

| Each of the young princesses

had a little plot of ground in the garden, where she

might dig and plant as she pleased. One arranged her

flower-bed into the form of a whale; another thought it

better to make hers like the figure of a little mermaid;

but that of the youngest was round like the sun, and

contained flowers as red as his rays at sunset. She was a

strange child, quiet and thoughtful; and while her

sisters would be delighted with the wonderful things

which they obtained from the wrecks of vessels, she cared

for nothing but her pretty red flowers, like the sun,

excepting a beautiful marble statue. It was the

representation of a handsome boy, carved out of pure

white stone, which had fallen to the bottom of the sea

from a wreck. She planted by the statue a rose-colored

weeping willow. It grew splendidly, and very soon hung

its fresh branches over the statue, almost down to the

blue sands. The shadow had a violet tint, and waved to

and fro like the branches; it seemed as if the crown of

the tree and the root were at play, and trying to kiss

each other. Nothing gave her so much pleasure as to hear about the world above the sea. She made her old grandmother tell her all she knew of the ships and of the towns, the people and the animals. To her it seemed most wonderful and beautiful to hear that the flowers of the land should have fragrance, and not those below the sea; that the trees of the forest should be green; and that the fishes among the trees could sing so sweetly, that it was quite a pleasure to hear them. Her grandmother called the little birds fishes, or she would not have understood her; for she had never seen birds. “When you have reached your fifteenth year,” said the grand-mother, “you will have permission to rise up out of the sea, to sit on the rocks in the moonlight, while the great ships are sailing by; and then you will see both forests and towns.” In the following year, one of the sisters would be fifteen: but as each was a year younger than the other, the youngest would have to wait five years before her turn came to rise up from the bottom of the ocean, and see the earth as we do. However, each promised to tell the others what she saw on her first visit, and what she thought the most beautiful; for their grandmother could not tell them enough; there were so many things on which they wanted information. None of them longed so much for her turn to come as the youngest, she who had the longest time to wait, and who was so quiet and thoughtful. Many nights she stood by the open window, looking up through the dark blue water, and watching the fish as they splashed about with their fins and tails. She could see the moon and stars shining faintly; but through the water they looked larger than they do to our eyes. When something like a black cloud passed between her and them, she knew that it was either a whale swimming over her head, or a ship full of human beings, who never imagined that a pretty little mermaid was standing beneath them, holding out her white hands towards the keel of their ship. As soon as the eldest was fifteen, she was allowed to rise to the surface of the ocean. When she came back, she had hundreds of things to talk about; but the most beautiful, she said, was to lie in the moonlight, on a sandbank, in the quiet sea, near the coast, and to gaze on a large town nearby, where the lights were twinkling like hundreds of stars; to listen to the sounds of the music, the noise of carriages, and the voices of human beings, and then to hear the merry bells peal out from the church steeples; and because she could not go near to all those wonderful things, she longed for them more than ever. Oh, did not the youngest sister listen eagerly to all these descriptions? and afterwards, when she stood at the open window looking up through the dark blue water, she thought of the great city, with all its bustle and noise, and even fancied she could hear the sound of the church bells, down in the depths of the sea. In another year the second sister received permission to rise to the surface of the water, and to swim about where she pleased. She rose just as the sun was setting, and this, she said, was the most beautiful sight of all. The whole sky looked like gold, while violet and rose-colored clouds, which she could not describe, floated over her; and, still more rapidly than the clouds, flew a large flock of wild swans towards the setting sun, looking like a long white veil across the sea. She also swam towards the sun; but it sunk into the waves, and the rosy tints faded from the clouds and from the sea. The third sister's turn followed; she was the boldest of them all, and she swam up a broad river that emptied itself into the sea. On the banks she saw green hills covered with beautiful vines; palaces and castles peeped out from amid the proud trees of the forest; she heard the birds singing, and the rays of the sun were so powerful that she was obliged often to dive down under the water to cool her burning face. In a narrow creek she found a whole troop of little human children, quite naked, and sporting about in the water; she wanted to play with them, but they fled in a great fright; and then a little black animal came to the water; it was a dog, but she did not know that, for she had never before seen one. This animal barked at her so terribly that she became frightened, and rushed back to the open sea. But she said she should never forget the beautiful forest, the green hills, and the pretty little children who could swim in the water, although they had not fish's tails. The fourth sister was more timid; she remained in the midst of the sea, but she said it was quite as beautiful there as nearer the land. She could see for so many miles around her, and the sky above looked like a bell of glass. She had seen the ships, but at such a great distance that they looked like sea-gulls. The dolphins sported in the waves, and the great whales spouted water from their nostrils till it seemed as if a hundred fountains were playing in every direction. The fifth sister's birthday occurred in the winter; so when her turn came, she saw what the others had not seen the first time they went up. The sea looked quite green, and large icebergs were floating about, each like a pearl, she said, but larger and loftier than the churches built by men. They were of the most singular shapes, and glittered like diamonds. She had seated herself upon one of the largest, and let the wind play with her long hair, and she remarked that all the ships sailed by rapidly, and steered as far away as they could from the iceberg, as if they were afraid of it. Towards evening, as the sun went down, dark clouds covered the sky, the thunder rolled and the lightning flashed, and the red light glowed on the icebergs as they rocked and tossed on the heaving sea. On all the ships the sails were reefed with fear and trembling, while she sat calmly on the floating iceberg, watching the blue lightning, as it darted its forked flashes into the sea. When first the sisters had permission to rise to the surface, they were each delighted with the new and beautiful sights they saw; but now, as grown-up girls, they could go when they pleased, and they had become indifferent about it. They wished themselves back again in the water, and after a month had passed they said it was much more beautiful down below, and pleasanter to be at home. Yet often, in the evening hours, the five sisters would twine their arms round each other, and rise to the surface, in a row. They had more beautiful voices than any human being could have; and before the approach of a storm, and when they expected a ship would be lost, they swam before the vessel, and sang sweetly of the delights to be found in the depths of the sea, and begging the sailors not to fear if they sank to the bottom. But the sailors could not understand the song, they took it for the howling of the storm. And these things were never to be beautiful for them; for if the ship sank, the men were drowned, and their dead bodies alone reached the palace of the Sea King. When the sisters rose, arm-in-arm, through the water in this way, their youngest sister would stand quite alone, looking after them, ready to cry, only that the mermaids have no tears, and therefore they suffer more. “Oh, were I but fifteen years old,” said she: “I know that I shall love the world up there, and all the people who live in it.” At last she reached her fifteenth year. “Well, now, you are grown up,” said the old dowager, her grandmother; “so you must let me adorn you like your other sisters;” and she placed a wreath of white lilies in her hair, and every flower leaf was half a pearl. Then the old lady ordered eight great oysters to attach themselves to the tail of the princess to show her high rank. “But they hurt me so,” said the little mermaid. “Pride must suffer pain,” replied the old lady. Oh, how gladly she would have shaken off all this grandeur, and laid aside the heavy wreath! The red flowers in her own garden would have suited her much better, but she could not help herself: so she said, “Farewell,” and rose as lightly as a bubble to the surface of the water. The sun had just set as she raised her head above the waves; but the clouds were tinted with crimson and gold, and through the glimmering twilight beamed the evening star in all its beauty. The sea was calm, and the air mild and fresh. A large ship, with three masts, lay becalmed on the water, with only one sail set; for not a breeze stiffed, and the sailors sat idle on deck or amongst the rigging. There was music and song on board; and, as darkness came on, a hundred colored lanterns were lighted, as if the flags of all nations waved in the air. The little mermaid swam close to the cabin windows; and now and then, as the waves lifted her up, she could look in through clear glass window-panes, and see a number of well-dressed people within. Among them was a young prince, the most beautiful of all, with large black eyes; he was sixteen years of age, and his birthday was being kept with much rejoicing. The sailors were dancing on deck, but when the prince came out of the cabin, more than a hundred rockets rose in the air, making it as bright as day. The little mermaid was so startled that she dived under water; and when she again stretched out her head, it appeared as if all the stars of heaven were falling around her, she had never seen such fireworks before. Great suns spurted fire about, splendid fireflies flew into the blue air, and everything was reflected in the clear, calm sea beneath. The ship itself was so brightly illuminated that all the people, and even the smallest rope, could be distinctly and plainly seen. And how handsome the young prince looked, as he pressed the hands of all present and smiled at them, while the music resounded through the clear night air. It was very late; yet the little mermaid could not take her eyes from the ship, or from the beautiful prince. The colored lanterns had been extinguished, no more rockets rose in the air, and the cannon had ceased firing; but the sea became restless, and a moaning, grumbling sound could be heard beneath the waves: still the little mermaid remained by the cabin window, rocking up and down on the water, which enabled her to look in. After a while, the sails were quickly unfurled, and the noble ship continued her passage; but soon the waves rose higher, heavy clouds darkened the sky, and lightning appeared in the distance. A dreadful storm was approaching; once more the sails were reefed, and the great ship pursued her flying course over the raging sea. The waves rose mountains high, as if they would have overtopped the mast; but the ship dived like a swan between them, and then rose again on their lofty, foaming crests. To the little mermaid this appeared pleasant sport; not so to the sailors. At length the ship groaned and creaked; the thick planks gave way under the lashing of the sea as it broke over the deck; the mainmast snapped asunder like a reed; the ship lay over on her side; and the water rushed in. The little mermaid now perceived that the crew were in danger; even she herself was obliged to be careful to avoid the beams and planks of the wreck which lay scattered on the water. At one moment it was so pitch dark that she could not see a single object, but a flash of lightning revealed the whole scene; she could see every one who had been on board excepting the prince; when the ship parted, she had seen him sink into the deep waves, and she was glad, for she thought he would now be with her; and then she remembered that human beings could not live in the water, so that when he got down to her father's palace he would be quite dead. But he must not die. So she swam about among the beams and planks which strewed the surface of the sea, forgetting that they could crush her to pieces. Then she dived deeply under the dark waters, rising and falling with the waves, till at length she managed to reach the young prince, who was fast losing the power of swimming in that stormy sea. His limbs were failing him, his beautiful eyes were closed, and he would have died had not the little mermaid come to his assistance. She held his head above the water, and let the waves drift them where they would. In the morning the storm had ceased; but of the ship not a single fragment could be seen. The sun rose up red and glowing from the water, and its beams brought back the hue of health to the prince's cheeks; but his eyes remained closed. The mermaid kissed his high, smooth forehead, and stroked back his wet hair; he seemed to her like the marble statue in her little garden, and she kissed him again, and wished that he might live. Presently they came in sight of land; she saw lofty blue mountains, on which the white snow rested as if a flock of swans were lying upon them. Near the coast were beautiful green forests, and close by stood a large building, whether a church or a convent she could not tell. Orange and citron trees grew in the garden, and before the door stood lofty palms. The sea here formed a little bay, in which the water was quite still, but very deep; so she swam with the handsome prince to the beach, which was covered with fine, white sand, and there she laid him in the warm sunshine, taking care to raise his head higher than his body. Then bells sounded in the large white building, and a number of young girls came into the garden. The little mermaid swam out farther from the shore and placed herself between some high rocks that rose out of the water; then she covered her head and neck with the foam of the sea so that her little face might not be seen, and watched to see what would become of the poor prince. She did not wait long before she saw a young girl approach the spot where he lay. She seemed frightened at first, but only for a moment; then she fetched a number of people, and the mermaid saw that the prince came to life again, and smiled upon those who stood round him. But to her he sent no smile; he knew not that she had saved him. This made her very unhappy, and when he was led away into the great building, she dived down sorrowfully into the water, and returned to her father's castle. She had always been silent and thoughtful, and now she was more so than ever. Her sisters asked her what she had seen during her first visit to the surface of the water; but she would tell them nothing. Many an evening and morning did she rise to the place where she had left the prince. She saw the fruits in the garden ripen till they were gathered, the snow on the tops of the mountains melt away; but she never saw the prince, and therefore she returned home, always more sorrowful than before. It was her only comfort to sit in her own little garden, and fling her arm round the beautiful marble statue which was like the prince; but she gave up tending her flowers, and they grew in wild confusion over the paths, twining their long leaves and stems round the branches of the trees, so that the whole place became dark and gloomy. At length she could bear it no longer, and told one of her sisters all about it. Then the others heard the secret, and very soon it became known to two mermaids whose intimate friend happened to know who the prince was. She had also seen the festival on board ship, and she told them where the prince came from, and where his palace stood. “Come, little sister,” said the other princesses; then they entwined their arms and rose up in a long row to the surface of the water, close by the spot where they knew the prince's palace stood. It was built of bright yellow shining stone, with long flights of marble steps, one of which reached quite down to the sea. Splendid gilded cupolas rose over the roof, and between the pillars that surrounded the whole building stood life-like statues of marble. Through the clear crystal of the lofty windows could be seen noble rooms, with costly silk curtains and hangings of tapestry; while the walls were covered with beautiful paintings which were a pleasure to look at. In the centre of the largest saloon a fountain threw its sparkling jets high up into the glass cupola of the ceiling, through which the sun shone down upon the water and upon the beautiful plants growing round the basin of the fountain. Now that she knew where he lived, she spent many an evening and many a night on the water near the palace. She would swim much nearer the shore than any of the others ventured to do; indeed once she went quite up the narrow channel under the marble balcony, which threw a broad shadow on the water. Here she would sit and watch the young prince, who thought himself quite alone in the bright moonlight. She saw him many times of an evening sailing in a pleasant boat, with music playing and flags waving. She peeped out from among the green rushes, and if the wind caught her long silvery-white veil, those who saw it believed it to be a swan, spreading out its wings. On many a night, too, when the fishermen, with their torches, were out at sea, she heard them relate so many good things about the doings of the young prince, that she was glad she had saved his life when he had been tossed about half-dead on the waves. And she remembered that his head had rested on her bosom, and how heartily she had kissed him; but he knew nothing of all this, and could not even dream of her. She grew more and more fond of human beings, and wished more and more to be able to wander about with those whose world seemed to be so much larger than her own. They could fly over the sea in ships, and mount the high hills which were far above the clouds; and the lands they possessed, their woods and their fields, stretched far away beyond the reach of her sight. There was so much that she wished to know, and her sisters were unable to answer all her questions. Then she applied to her old grandmother, who knew all about the upper world, which she very rightly called the lands above the sea. “If human beings are not drowned,” asked the little mermaid, “can they live forever? do they never die as we do here in the sea?” “Yes,” replied the old lady, “they must also die, and their term of life is even shorter than ours. We sometimes live to three hundred years, but when we cease to exist here we only become the foam on the surface of the water, and we have not even a grave down here of those we love. We have not immortal souls, we shall never live again; but, like the green sea-weed, when once it has been cut off, we can never flourish more. Human beings, on the contrary, have a soul which lives forever, lives after the body has been turned to dust. It rises up through the clear, pure air beyond the glittering stars. As we rise out of the water, and behold all the land of the earth, so do they rise to unknown and glorious regions which we shall never see.” “Why have not we an immortal soul?” asked the little mermaid mournfully; “I would give gladly all the hundreds of years that I have to live, to be a human being only for one day, and to have the hope of knowing the happiness of that glorious world above the stars.” “You must not think of that,” said the old woman; “we feel ourselves to be much happier and much better off than human beings.” “So I shall die,” said the little mermaid, “and as the foam of the sea I shall be driven about never again to hear the music of the waves, or to see the pretty flowers nor the red sun. Is there anything I can do to win an immortal soul?” “No,” said the old woman, “unless a man were to love you so much that you were more to him than his father or mother; and if all his thoughts and all his love were fixed upon you, and the priest placed his right hand in yours, and he promised to be true to you here and hereafter, then his soul would glide into your body and you would obtain a share in the future happiness of mankind. He would give a soul to you and retain his own as well; but this can never happen. Your fish's tail, which amongst us is considered so beautiful, is thought on earth to be quite ugly; they do not know any better, and they think it necessary to have two stout props, which they call legs, in order to be handsome.” Then the little mermaid sighed, and looked sorrowfully at her fish's tail. “Let us be happy,” said the old lady, “and dart and spring about during the three hundred years that we have to live, which is really quite long enough; after that we can rest ourselves all the better. This evening we are going to have a court ball.” |

Chiu el la malgrandaj

reghidinoj havis en la ghardeno sian apartan loketon, kie

shi povis lau sia placho kaj bontrovo fosi kaj planti.

Unu donis al sia florejo la formon de baleno; alia trovis

pli bone, ke shia florejo similas je virineto de maro;

sed la plej juna donis al la sia formon rondan, kiel la

suno, kaj havis nur florojn rughe brilantajn, kiel tiu.

Shi estis en chio originala infano, silenta kaj pensanta,

kaj kiam la aliaj fratinoj sin ornamis per la mirindaj

objektoj, kiujn ili ricevis de shipoj, venintaj al la

fundo, shi volis havi, krom la rughaj floroj, kiuj

similis je la suno, nur unu belan statuon, kiu prezentis

tre belan knabon. Ghi estis farita el blanka klara

marmoro kaj falis sur la fundon de la maro che la

rompigho de shipo. Shi plantis apud la statuo rozarughan

salikon, kiu kreskis belege kaj tenis siajn branchojn

super la statuo, ghis la blua sablo de la fundo; kie la

ombro havis koloron nigrabluan kaj movadis sin senchese,

kiel la branchoj. Ghi elrigardis, kiel la supro kaj la

radikoj ludus inter si kaj sin kisus. Ne estis pli granda plezuro por la juna reghidino, ol audi pri la mondo supra kaj la homoj. La maljuna avino devis rakontadi chion, kion shi sciis pri shipoj kaj urboj, homoj kaj bestoj. Sed la plej bela kaj mirinda estis por si, ke la floroj supre sur la tero odoras, kion ne faras la floroj sur la fundo de la maro, kaj ke la arbaroj estas verdaj kaj la fishoj, kiujn oni vidas tie inter la branchoj, tiel laute kaj agrable kantas, ke estas plezuro ilin audi. Ghi estis la birdetoj, kiujn la avino nomis fishoj, char alie shiaj nepinoj, kiuj ne vidis ankorau birdojn, ne povus shin kompreni. “Kiam vi atingos la aghon de dekkvin jaroj,” diris la avino, “vi ricevos la permeson sin levi el la maro, sidi sub la lumo de la luno sur la maraj shtonegoj kaj rigardi la grandajn shipojn, kiuj veturos antau vi; vi vidos ankau arbarojn kaj urbojn!” Baldau unu el la fratinoj devis atingi la aghon de dekkvin jaroj, sed la aliaj.... chiu el ili estis unu jaron pli juna, ol la alia, tiel ke al la plej juna mankis ankorau plenaj kvin jaroj, ghis shi povus sin levi de la fundo de la maro kaj vidi, kiel nia mondo elrigardas. Sed unu promesis al la alia rakonti al shi, kion shi vidis kaj kio la plej multe plachis al shi en la unua tago; char ilia avino ne sufiche ankorau rakontis al ili, estis ankorau multaj aferoj, pri kiuj ili volus scii. Sed neniu el ili estis tiel plena je deziroj, kiel la plej juna, ghuste shi, kiu devis ankorau la plej longe atendi kaj estis tiel silenta kaj plena je pensoj. Ofte en la nokto shi staris antau la malfermita fenestro kaj rigardis supren tra la mallume blua akvo, kiel la fishoj per siaj naghiloj kaj vostoj ghin batis. La lunon kaj stelojn shi povis vidi; ili shajnis tre palaj, sed por tio ili tra la akvo elrigardis multe pli grandaj, ol antau niaj okuloj. Se sub ili glitis io kiel nigra nubo, shi sciis, ke tio chi estas au baleno naghanta super shi, au ech shipo kun multaj homoj. Ili certe ne pensis, ke bela virineto de maro staras sur la fundo kaj eltiras siajn blankajn manojn kontrau la shipo. Jen la plej maljuna reghidino atingis la aghon de dekkvin jaroj kaj ricevis la permeson sin levi super la suprajhon de la maro. Kiam shi revenis, shi havis multege por rakonti; sed la plej bela estas, shi diris, kushi en la lumo de la luno sur supermara sablajho sur trankvila maro kaj rigardi la grandan urbon, kiu sin trovas tuj sur la bordo de la maro, belan urbon, kie la lumoj brilas kiel centoj da steloj, audi la muzikon kaj la bruon de kaleshoj kaj homoj, vidi la multajn preghejojn kaj turojn kaj auskulti la sonadon de la preghejaj sonoriloj. Ghuste, char al la plej juna estis ankorau longe malpermesite sin levi, shi la plej multe sentis grandan deziregon je chio chi. Kun kia atento shi auskultis tiujn chi rakontojn! Kaj kiam shi poste je la vespero staris antau la malfermita fenestro kaj rigardis tra la mallume blua akvo, chiuj shiaj pensoj estis okupitaj je la granda urbo kun ghia bruado, kaj shajnis al shi, ke la sonado de la preghejaj sonoriloj trapenetras malsupren al shi. Post unu jaro la dua fratino ricevis la permeson sin levi tra la akvo kaj naghi kien shi volas. Shi suprennaghis che la subiro de la suno, kaj tiu chi vido lau shia opinio estis la plej bela. La tuta chielo elrigardis kiel oro, shi diris, kaj la nuboj – ha, ilian belecon shi ne povus sufiche bone priskribi! Rughaj kaj nigrabluaj ili sin transportis super shi, sed multe pli rapide ol ili, flugis, kiel longa blanka kovrilo, amaso da sovaghaj cignoj super la akvo al la forighanta suno. Ili flugis al la suno, sed tiu chi mallevighis kaj la roza brilo estingighis sur la maro kaj la nuboj. En la sekvanta jaro la tria fratino sin levis; shi estis la plej kuragha el chiuj kaj naghis tial supren en unu larghan riveron, kiu fluas al la maro. Palacoj kaj vilaghaj dometoj estis vidataj tra belegaj arbaroj. Shi audis kiel chiuj birdoj kantis, kaj la suno lumis tiel varme, ke shi ofte devis naghi sub la akvon, por iom malvarmigi sian brule varmeghan vizaghon. En unu malgranda golfo shi renkontis tutan amason da belaj homaj infanoj; ili kuradis tute nudaj kaj batadis en la akvo. Shi volis ludi kun ili, sed kun teruro ili forkuris. Poste venis malgranda nigra besto, tio estis hundo, sed shi antaue neniam vidis hundon; tiu chi komencis tiel furioze shin boji, ke shi tute ektimighis kaj ree forkuris en la liberan maron. Sed neniam shi forgesos la belegajn arbarojn, la verdajn montetojn kaj la malgrandajn infanojn, kiuj povis naghi, kvankam ili ne havis fishan voston. La kvara fratino ne estis tiel kuragha; shi restis en la mezo de la sovagha maro kaj rakontis, ke ghuste tie estas la plej bele. Oni povas rigardi tre malproksime chirkaue, kaj la chielo staras kiel vitra klosho super la maro. Shipojn shi vidis, sed nur tre malproksime, ili elrigardis kiel mevoj; la ludantaj delfenoj sin renversadis kaj la grandaj balenoj shprucis akvon el la truoj de siaj nazoj supren, ke ghi elrigardis chirkaue kiel centoj da fontanoj. Nun venis la tempo por la kvina fratino. Shia naskotago estis ghuste en la mezo de vintro, kaj tial shi vidis, kion la aliaj la unuan fojon ne vidis. La maro estis preskau tute verda, kaj chirkaue naghis grandaj montoj de glacio, el kiuj, lau shia rakonto, chiu elrigardis kiel perlo kaj tamen estis multe pli granda ol la turoj, kiujn la homoj konstruas. En la plej mirindaj formoj ili sin montris kaj brilis kiel diamantoj. Shi sidighis sur unu el la plej grandaj, kaj chiuj shipistoj forkuradis kun teruro de la loko, kie shi sidis kaj lasis la venton ludi kun shiaj longaj haroj. Sed je la vespero la chielo kovrighis je nuboj, ghi tondris kaj fulmis, dum la nigra maro levis la grandajn pecegojn da glacio alte supren kaj briligis ilin en la forta fulmado. Sur chiuj sipoj oni mallevis la velojn; estis timego, teruro, sed shi sidis trankvile sur sia naghanta glacia monto kaj vidis, kiel la fajraj fulmoj zigzage sin jhetadis en la shauman maron. Kiam iu el la fratinoj venis la unuan fojon super la akvon, chiu estis ravata de la nova kaj bela, kiun shi vidis; sed nun, kiam ili kiel grandaghaj knabinoj havis la permeson supreniri chiufoje lau sia volo, ghi farighis por ili indiferenta; ili deziregis ree hejmen, kaj post la paso de unu monato ili diris, ke malsupre en la domo estas la plej bele kaj tie oni sin sentas la plej oportune. Ofte en vespera horo la kvin fratinoj chirkauprenadis unu la alian per la manoj kaj suprennaghadis en unu linio super la akvon. Ili havis belegajn vochojn, pli belajn ol la vocho de homo, kaj kiam ventego komencighis kaj ili povis supozi, ke rompighos shipoj, ili naghadis antau la shipoj kaj kantadis agrable pri la beleco sur la fundo de la maro, kaj petis la shipanojn ne timi veni tien. Sed tiuj chi ne povis kompreni la vortojn, ili pensis ke ghi estas la ventego; kaj ili ankau ne povis vidi la belajhojn de malsupre, char se la shipo iris al la fundo, la homoj mortis en la akvo kaj venis nur jam kiel malvivuloj en la palacon de la regho de la maro. Kiam je la vespero la fratinoj tiel mano en mano sin alte levis tra la maro, tiam la malgranda fratino restis tute sola kaj rigardis post ili, kaj estis al shi, kiel shi devus plori; sed virino de maro ne havas larmojn, kaj tial shi suferas multe pli multe. “Ho, se mi jam havus la aghon de dekkvin jaroj!” shi diris. “Mi scias, ke ghuste mi forte amos la mondon tie supre kaj la homojn, kiuj tie loghas kaj konstruas!” Fine shi atingis la aghon de dekkvin jaroj. “Jen vi elkreskis,” diris shia avino, la maljuna reghinovidvino. “Venu, kaj mi vin ornamos kiel viajn aliajn fratinojn!” Shi metis al shi kronon el blankaj lilioj sur la harojn, sed chiu folieto de floro estis duono de perlo; kaj la maljuna avino lasis almordighi al la vosto de la reghidino ok grandajn ostrojn, por montri shian altan staton. “Tio chi doloras!” diris la virineto de maro. “Jes, kortega ceremonio postulas maloportunecon!” diris la avino. Ho, shi fordonus kun plezuro chiun chi belegajhon kaj dejhetus la multepezan kronon! Shiaj rughaj ghardenaj floroj staris al shi multe pli bone, sed nenio helpis. “Adiau!” shi diris kaj levis sin facile kaj bele tra la akvo. Antau momento subiris la suno, kiam shi levis la kapon super la suprajho de la maro; sed chiuj nuboj brilis ankorau kiel rozoj kaj oro, kaj tra la palrugha aero lumis la stelo de la vespero, la aero estis trankvila kaj fresha kaj nenia venteto movis la maron. Sur la maro staris granda trimasta shipo, nur unu velo estis levita, char estis nenia bloveto, kaj inter la shnuregaro sidis chie shipanoj. Oni audis muzikon kaj kantadon, kaj kiam la vespero farighis pli malluma, centoj da koloraj lanternoj estis ekbruligitaj; ghi elrigardis, kvazau la flagoj de chiuj nacioj blovighas en la aero. La virineto de maro alnaghis ghis la fenestro de la kajuto, kaj chiufoje, kiam la akvo sin levis, shi provis rigardi tra la klaraj vitroj de la fenestroj en la kajuton, kie staris multaj ornamitaj homoj, sed la plej bela el ili estis la juna reghido kun la grandaj nigraj okuloj. Li povis havi la aghon de dekses jaroj, lia tago de naskigho ghuste nun estis festata, kaj pro tio chi regis la tuta tiu gajeco kaj belegeco. La shipanoj dancis sur la ferdeko, kaj kiam la reghido al ili eliris, pli ol cent raketoj levighis en la aeron. Ili lumis kiel luma tago, tiel ke la virineto de maro ektimis kaj subighis sub la akvon, Sed baldau shi denove ellevis la kapon kaj tiam shajnis al shi, kvazau chiuj steloj de la chielo defalas al shi. Neniam ankorau shi vidis tian fajrajhon. Grandaj sunoj mughante sin turnadis, belegaj fajraj fishoj sin levadis en la bluan aeron kaj de chio estis vidata luma rebrilo en la klara trankvila maro. Sur la shipo mem estis tiel lume, ke oni povis vidi ech la plej malgrandan shnuron, ne parolante jam pri la homoj. Kiel bela la juna reghido estis, kaj li premis al la homoj la manojn kun afabla ridetado, dum la muziko sonis tra la bela nokto. Jam farighis malfrue, sed la virineto de maro ne povis deturni la okulojn de la shipo kaj de la bela reghido. La koloraj lanternoj estingighis, la raketoj sin ne levadis pli en la aeron, la pafilegoj jam pli ne tondris, sed profunde en la maro estis movado kaj bruado. La virineto de maro sidis sur la akvo kaj balancighis supren kaj malsupren, tiel ke shi povis enrigardadi en la kajuton. Sed pli rapide la shipo kuris super la ondoj, unu velo post la alia estis levataj, pli forte batis la ondoj, nigra nubego sin montris kaj fulmoj malproksimaj ekbrilis. Terura ventego baldau komencighis. Tial la shipanoj demetis la velojn. La granda shipo balancighis en rapidega kurado sur la sovagha maro; kiel grandaj nigraj montoj sin levadis la shaumanta akvo, minacante sin transjheti super la mastoj, sed la shipo sin mallevadis kiel cigno inter la altaj ondoj kaj levadis sin ree sur la akvajn montojn. Al la virineto de maro ghi sajnis kiel veturo de plezuro, sed la shipanoj tute alie tion chi rigardis; la shipo ghemegis kaj krakis, la chefa masto rompighis en la mezo kiel kano, kaj la shipo kushighis sur flanko kaj la akvo eniris en la internajhon de la shipo. Nun la virineto de maro vidis, ke la shipanoj estas en danghero, shi devis sin mem gardi antau la traboj kaj rompajhoj de la shipo, kiuj estis pelataj super la akvo. Kelkan tempon estis tiel mallumege, ke shi nenion povis vidi; sed jen ekfulmis kaj farighis denove tiel lume, ke la virineto de maro klare revidis chiujn sur la shipo. Chiu penis sin savi, kiel li povis. La plej multe shi observadis la junan reghidon kaj shi vidis, kiam la shipo rompighis, ke li falis en la profundan maron. En la unua momento shi estis tre ghoja, char nun li ja venos al shi, sed baldau venis al shi en la kapon, ke la homoj ja ne povas vivi en la akvo kaj tiel li nur malviva venos en la palacon de la regho de la maro. Ne, morti li ne devas! Tial la virineto de maro eknaghis inter la traboj kaj tabuloj, kiuj kuradis sur la maro, forgesis la propran dangheron, subnaghis profunde en la akvon kaj sin levis denove inter la altaj ondoj. Fine shi atingis la junan reghidon, kiu jam apenau sin tenis sur la suprajho de la sovagha maro. Liaj manoj kaj piedoj komencis jam lacighi, la belaj okuloj sin fermis, li devus morti, se shi ne alvenus. Shi tenis lian kapon super la akvo kaj lasis shin peli de la ondoj, kien ili volis. Chirkau la mateno la ventego finighis. De la shipo ne restis ech unu ligneto. Rugha kaj brilanta sin levis la suno el la akvo, kaj shajnis, ke per tio chi la vangoj de la reghido ricevis vivon, tamen liaj okuloj restis fermitaj. La virineto de maro kisis lian altan belan frunton kaj reordigis liajn malsekajn harojn. Shajnis al shi, ke li estas simila je la marmora statuo en shia malgranda ghardeno. Shi lin kisis kaj rekisis kaj forte deziris, ke li restu viva. Jen montrighis tero, altaj bluaj montoj, sur kies suproj brilis la blanka negho, kiel amaso da cignoj. Malsupre sur la bordo staris belegaj verdaj arbaroj kaj antau ili staris preghejo au monahhejo, estis ankorau malfacile bone ghin diferencigi, sed konstruo ghi estis. Citronaj kaj oranghaj arboj kreskis en la ghardeno, kaj antau la eniro staris altaj palmoj. La maro faris tie chi malgrandan golfeton, en kiu la akvo estis tute trankvila, sed tre profunda, kaj kiu estis limita de superakvaj shtonegoj, kovritaj de delikata blanka sablo. Tien chi alnaghis la virineto de maro kun la bela princo, kushigis lin sur la sablo kaj zorgis, ke lia kapo kushu alte en la varma lumo de la suno. Eksonis la sonoriloj en la granda blanka konstruo kaj multaj junaj knabinoj sin montris en la ghardeno. Tiam la virineto de maro fornaghis kaj kashis sin post kelkaj altaj shtonoj, kiuj elstaris el la akvo, kovris la harojn kaj bruston per shaumo de la maro, tiel ke neniu povis vidi shian belan vizaghon, kaj shi nun observadis, kiu venos al la malfelica reghido. Ne longe dauris, kaj alvenis juna knabino. Shi videble forte ektimis, sed nur unu momenton, kaj baldau shi vokis multajn homojn, kaj la virineto de maro vidis, ke la reghido denove ricevis la konscion kaj ridetis al chiuj chirkaustarantoj, sed al sia savintino li ne ridetis, li ja ech ne sciis, ke al shi li devas danki la vivon. Shi sentis sin tiel malghoja, ke shi, kiam oni lin forkondukis en la grandan konstruon, malgaje subnaghis sub la akvon kaj revenis al la palaco de sia patro. Shi estis chiam silenta kaj enpensa, sed nun ghi farighis ankorau pli multe. La fratinoj shin demandis, kion shi vidis la unuan fojon tie supre, sed shi nenion al ili rakontis. Ofte en vespero kaj mateno shi levadis sin al la loko, kie shi forlasis la reghidon. Shi vidis, kiel la fruktoj de la ghardeno farighis maturaj kaj estis deshiritaj, shi vidis, kiel la negho fluidighis sur la altaj montoj, sed la reghidon shi ne vidis, kaj chiam pli malghoja shi tial revenadis hejmen. Shia sola plezuro estis sidi en sia ghardeneto kaj chirkaupreni per la brakoj la belan marmoran statuon, kiu estis simila je la reghido; sed siajn florojn shi ne flegis, kaj sovaghe ili kreskis super la vojetoj, kaj iliaj longaj trunketoj kaj folioj sin kunplektis kun la branchoj de la arboj tiel, ke tie farighis tute mallume. Fine shi ne povis pli elteni kaj rakontis al unu el siaj fratinoj, kaj baldau tiam sciighis chiuj aliaj, sed je vorto de honoro neniu pli ol tiu, kaj kelkaj aliaj virinetoj de maro, kiuj tamen rakontis ghin nur al siaj plej proksimaj amikinoj. Unu el ili povis doni sciajhon pri la reghido, shi ankau vidis la feston naskotagan sur la shipo, sciis, de kie la reghido estas kaj kie sin trovas lia regno. “Venu, fratineto!” diris la aliaj reghidinoj, kaj interplektinte la brakojn reciproke post la shultroj, ili sin levis en longa linio el la maro tien, kie sin trovis la palaco de la reghido. Tiu chi palaco estis konstruita el helflava brilanta speco de shtono, kun grandaj marmoraj shtuparoj, el kiuj unu kondukis rekte en la maron. Belegaj orkovritaj kupoloj sin levadis super la tegmentoj, kaj inter la kolonoj, kiuj chirkauis la tutan konstruon, staris marmoraj figuroj, kiuj elrigardis kiel vivaj ekzistajhoj. Tra la klara vitro en la altaj fenestroj oni povis rigardi en la plej belegajn salonojn, kie pendis multekostaj silkaj kurtenoj kaj tapishoj kaj chiuj muroj estis ornamitaj per grandaj pentrajhoj, ke estis efektiva plezuro chion tion chi vidi. En la mezo de la granda salono batis alta fontano, ghiaj radioj sin levadis ghis la vitra kupolo de la plafono, tra kiu la suno lumis sur la akvo kaj la plej belaj kreskajhoj, kiuj sin trovis en la granda baseno. Nun shi sciis, kie li loghas, kaj tie shi montradis sin ofte en vespero kaj en nokto sur la akvo; shi alnaghadis multe pli proksime al la tero, ol kiel kuraghus iu alia, shi ech sin levadis tra la tuta mallargha kanalo, ghis sub la belega marmora balkono. Tie shi sidadis kaj rigardadis la junan reghidon, kiu pensis, ke li sidas sola en la klara lumo de la luno. Ofte en vespero shi vidadis lin forveturantan sub la sonoj de muziko en lia belega shipeto ornamita per flagoj; shi rigardadis tra la verdaj kanoj; kaj se la vento kaptadis shian longan blankan vualon kaj iu shin vidis, li pensis, ke ghi estas cigno, kiu disvastigas la flugilojn. Ofte en la nokto, kiam la fishistoj kaptadis fishojn sur la maro che lumo de torchoj, shi audadis, ke ili rakontas multon da bona pri la juna reghido, kaj shi ghojadis, ke shi savis al li la vivon, kiam li preskau sen vivo estis pelata de la ondoj, kaj shi ekmemoradis, kiel firme lia kapo ripozis sur shia brusto kaj kiel kore shi lin kisis. Pri tio chi li nenion sciis, li ne povis ech songhi pri shi. Chiam pli kaj pli kreskis shia amo al la homoj, chiam pli shi deziris povi sin levi al ili kaj vivi inter ili, kaj ilia mondo shajnis al shi multe pli granda ol shia. Ili ja povas flugi sur shipoj trans la maron, sin levi sur la altajn montojn alte super la nubojn, kaj la landoj, kiujn ili posedas, sin etendas kun siaj arbaroj kaj kampoj pli malproksime, ol shi povas atingi per sia rigardo. Multon shi volus scii, sed la fratinoj ne povis doni al shi respondon je chio, kaj tial shi demandadis pri tio la maljunan avinon, kiu bone konis la pli altan mondon, kiel shi nomadis la landojn super la maro. “Se la homoj ne dronas”, demandis la virineto de maro, “chu ili tiam povas vivi eterne, chu ili ne mortas, kiel ni tie chi sur la fundo de la maro?” “Ho jes”, diris la maljunulino, “ili ankau devas morti, kaj la tempo de ilia vivo estas ankorau pli mallonga ol de nia. Ni povas atingi la aghon de tricent jaroj, sed kiam nia vivo chesighas, ni turnighas en shaumon kaj ni ne havas tie chi ech tombon inter niaj karaj. Ni ne havas senmortan animon, ni jam neniam revekighas al vivo, ni similas je la verda kreskajho, kiu, unu fojon detranchita, jam neniam pli povas revivighi. Sed la homoj havas animon, kiu vivas eterne, kiam la korpo jam refarighis tero. La animo sin levas tra la etero supren, al la brilantaj steloj! Tute tiel, kiel ni nin levas el la maro kaj rigardas la landojn de la homoj, tiel ankau ili sin levas al nekonataj belegaj lokoj, kiujn ni neniam povos vidi.” “Kial ni ne ricevis senmortan animon?” malghoje demandis la virineto de maro. “Kun plezuro mi fordonus chiujn centojn da jaroj, kiujn mi povas vivi, por nur unu tagon esti homo kaj poste preni parton en la chiela mondo!” “Pri tio chi ne pensu!” diris la maljunulino, “nia sorto estas multe pli felicha kaj pli bona, ol la sorto de la homoj tie supre!” “Sekve mi mortos kaj disfluighos kiel shaumo sur la maro, mi jam ne audados la muzikon de la ondoj, ne vidados pli la belajn florojn kaj la luman sunon! Chu mi nenion povas fari, por ricevi eternan animon?” “Ne!” diris la maljunulino, “nur se homo vin tiel ekamus, ke vi estus por li pli ol patro kaj patrino, se li alligighus al vi per chiuj siaj pensoj kaj sia amo kaj petus, ke la pastro metu lian dekstran manon en la vian kun la sankta promeso de fideleco tie chi kaj chie kaj eterne, tiam lia animo transfluus en vian korpon kaj vi ankau ricevus parton en la felicho de la homoj. Li donus al vi animon kaj retenus tamen ankau sian propran. Sed tio chi neniam povas farighi! Ghuste tion, kio tie chi en la maro estas nomata bela, vian voston de fisho, ili tie supre sur la tero trovas malbela. Char mankas al ili la ghusta komprenado, tie oni devas havi du malgraciajn kolonojn, kiujn ili nomas piedoj, por esti nomata bela!” La virineto de maro ekghemis kaj rigardis malghoje sian fishan voston. “Ni estu gajaj!” diris la maljunulino, “ni saltadu kaj dancadu en la tricent jaroj, kiujn la sorto al ni donas; ghi estas certe suficha tempo, poste oni tiom pli senzorge povas ripozi. Hodiau vespere ni havos balon de kortego!” |

Далеко в море вода синяя-синяя, как лепестки самых красивых васильков, и прозрачная-прозрачная, как самое чистое стекло, только очень глубока, так глубока, что никакого якорного каната не хватит. Много колоколен надо поставить одну на другую, тогда только верхняя выглянет на поверхность. Там на дне живет подводный народ.

Только не подумайте, что дно голое, один только белый песок. Нет, там растут невиданные деревья и цветы с такими гибкими стеблями и листьями, что они шевелятся, словно живые, от малейшего движения воды. А между ветвями снуют рыбы, большие и маленькие, совсем как птицы в воздухе у нас наверху. В самом глубоком месте стоит дворец морского царя - стены его из кораллов, высокие стрельчатые окна из самого чистого янтаря, а крыша сплошь раковины; они то открываются, то закрываются, смотря по тому, прилив или отлив, и это очень красиво, ведь в каждой лежат сияющие жемчужины и любая была бы великим украшением в короне самой королевы.

Царь морской давным-давно овдовел, и хозяйством у него заправляла старуха мать, женщина умная, только больно уж гордившаяся своей родовитостью: на хвосте она носила целых двенадцать устриц, тогда как прочим вельможам полагалось только шесть. В остальном же она заслуживала всяческой похвалы, особенно потому, что души не чаяла в своих маленьких внучках - принцессах. Их было шестеро, все прехорошенькие, но милее всех самая младшая, с кожей чистой и нежной, как лепесток розы, с глазами синими и глубокими, как море. Только у нее, как, впрочем, и у остальных, ног не было, а вместо них был хвост, как у рыб.

День-деньской играли принцессы во дворце, в просторных палатах, где из стен росли живые цветы. Раскрывались большие янтарные окна, и внутрь вплывали рыбы, совсем как у нас ласточки влетают в дом, когда окна стоят настежь, только рыбы подплывали прямо к маленьким принцессам, брали из их рук еду и позволяли себя гладить.

Перед дворцом был большой сад, в нем росли огненно-красные и темно-синие деревья, плоды их сверкали золотом, цветы - горячим огнем, а стебли и листья непрестанно колыхались. Земля была сплошь мелкий песок, только голубоватый, как серное пламя. Все там внизу отдавало в какую-то особенную синеву, - впору было подумать, будто стоишь не на дне морском, а в воздушной вышине, и небо у тебя не только над головой, но и под ногами, В безветрие со дна видно было солнце, оно казалось пурпурным цветком, из чаши которого льется свет.

У каждой принцессы было в саду свое местечко, здесь они могли копать и сажать что угодно. Одна устроила себе цветочную грядку в виде кита, другой вздумалось, чтобы ее грядка гляделась русалкой, а самая младшая сделала себе грядку, круглую, как солнце, и цветы на ней сажала такие же алые, как оно само. Странное дитя была эта русалочка, тихое, задумчивое. Другие сестры украшали себя разными разностями, которые находили на потонувших кораблях, а она только и любила, что цветы ярко-красные, как солнце, там, наверху, да еще красивую мраморную статую. Это был прекрасный мальчик, высеченный из чистого белого камня и спустившийся на дно морское после кораблекрушения. Возле статуи русалочка посадила розовую плакучую иву, она пышно разрослась и свешивала свои ветви над статуей к голубому песчаному дну, где получалась фиолетовая тень, зыблющаяся в лад колыханию ветвей, и от этого казалось, будто верхушка и корни ластятся друг к другу.

Больше всего русалочка любила слушать рассказы о мире людей там, наверху. Старой бабушке пришлось рассказать ей все, что она знала о кораблях и городах, о людях и животных. Особенно чудесным и удивительным казалось русалочке то, что цветы на земле пахнут, - не то что здесь, на морском дне, - леса там зеленые, а рыбы среди ветвей поют так громко и красиво, что просто заслушаешься. Рыбами бабушка называла птиц, иначе внучки не поняли бы ее: они ведь сроду не видывали птиц.

- Когда вам исполнится пятнадцать лет, - говорила бабушка, - вам дозволят всплывать на поверхность, сидеть в лунном свете на скалах и смотреть на плывущие мимо огромные корабли, на лесами города!

В этот год старшей принцессе как раз исполнялось пятнадцать лет, но сестры были погодки, и выходило так, что только через пять лет самая младшая сможет подняться со дна морского и увидеть, как живется нам здесь, наверху. Но каждая обещала рассказать остальным, что она увидела и что ей больше всего понравилось в первый день, - рассказов бабушки им было мало, хотелось знать побольше.

Ни одну из сестер не тянуло так на поверхность, как самую младшую, тихую, задумчивую русалочку, которой приходилось ждать дольше всех. Ночь за ночью проводила она у открытого окна и все смотрела наверх сквозь темно-синюю воду, в которой плескали хвостами и плавниками рыбы. Месяц и звезды виделись ей, и хоть светили они совсем бледно, зато казались сквозь воду много больше, чем нам. А если под ними скользило как бы темное облако, знала она, что это либо кит проплывает, либо корабль, а на нем много людей, и, уж конечно, им и в голову не приходило, что внизу под ними хорошенькая русалочка тянется к кораблю своими белыми руками.

И вот старшей принцессе исполнилось пятнадцать лет, и ей позволили всплыть на поверхность.

Сколько было рассказов, когда она вернулась назад! Ну, а лучше всего, рассказывала она, было лежать в лунном свете на отмели, когда море спокойно, и рассматривать большой город на берегу: точно сотни звезд, там мерцали огни, слышалась музыка, шум экипажей, говор людей, виднелись колокольни и шпили, звонили колокола. И как раз потому, что туда ей было нельзя, туда и тянуло ее больше всего.

Как жадно внимала ее рассказам самая младшая сестра! А потом, вечером, стояла у открытого окна и смотрела наверх сквозь темно-синюю воду и думала о большом городе, шумном и оживленном, и ей казалось даже, что она слышит звон колоколов.

Через год и второй сестре позволили подняться на поверхность и плыть куда угодно. Она вынырнула из воды как раз в ту минуту, когда солнце садилось, и решила, что прекраснее зрелища нет на свете. Небо было сплошь золотое, сказала она, а облака - ах, у нее просто нет слов описать, как они красивы! Красные и фиолетовые, плыли они по небу, но еще быстрее неслась к солнцу, точно длинная белая вуаль, стая диких лебедей. Она тоже поплыла к солнцу, но оно погрузилось в воду, и розовый отсвет на море и облаках погас.

Еще через год поднялась на поверхность третья сестра. Эта была смелее всех и проплыла в широкую реку, которая впадала в море. Она увидела там зеленые холмы с виноградниками, а из чащи чудесного леса выглядывали дворцы и усадьбы. Она слышала, как поют птицы, а солнце пригревало так сильно, что ей не раз приходилось нырять в воду, чтобы остудить свое пылающее лицо. В бухте ей попалась целая стая маленьких человеческих детей, они бегали нагишом и плескались в воде. Ей захотелось поиграть с ними, но они испугались ее и убежали, а вместо них явился какой-то черный зверек - это была собака, только ведь ей еще ни разу не доводилось видеть собаку - и залаял на нее так страшно, что она перепугалась и уплыла назад в море. Но никогда не забыть ей чудесного леса, зеленых холмов и прелестных детей, которые умеют плавать, хоть и нет у них рыбьего хвоста.

Четвертая сестра не была такой смелой, она держалась в открытом море и считала, что там-то и было лучше всего: море видно вокруг на много-много миль, небо над головой как огромный стеклянный купол. Видела она и корабли, только совсем издалека, и выглядели они совсем как чайки, а еще в море кувыркались резвые дельфины и киты пускали из ноздрей воду, так что казалось, будто вокруг били сотни фонтанов.

Дошла очередь и до пятой сестры. Ее день рождения был зимой, и поэтому она увидела то, чего не удалось увидеть другим. Море было совсем зеленое, рассказывала она, повсюду плавали огромные ледяные горы, каждая ни дать ни взять жемчужина, только куда выше любой колокольни, построенной людьми. Они были самого причудливого вида и сверкали, словно алмазы. Она уселась на самую большую из них, ветер развевал ее длинные волосы, и моряки испуганно обходили это место подальше. К вечеру небо заволоклось тучами, засверкали молнии, загремел гром, почерневшее море вздымало ввысь огромные ледяные глыбы, озаряемые вспышками молний. На кораблях убирали паруса, вокруг был страх и ужас, а она как ни в чем не бывало плыла на своей ледяной горе и смотрела, как молнии синими зигзагами ударяют в море.

Так вот и шло: выплывает какая-нибудь из сестер первый раз на поверхность, восхищается всем новым и красивым, ну, а потом, когда взрослой девушкой может подниматься наверх в любую минуту, все становится ей неинтересно и она стремится домой и уже месяц спустя говорит, что у них внизу лучше всего, только здесь и чувствуешь себя дома.

Часто по вечерам, обнявшись, всплывали пять сестер на поверхность. У всех были дивные голоса, как ни у кого из людей, и когда собиралась буря, грозившая гибелью кораблям, они плыли перед кораблями и пели так сладко о том, как хорошо на морском дне, уговаривали моряков без боязни спуститься вниз. Только моряки не могли разобрать слов, им казалось, что это просто шумит буря, да и не довелось бы им увидеть на дне никаких чудес - когда корабль тонул, люди захлебывались и попадали во дворец морского царя уже мертвыми.

Младшая же русалочка, когда сестры ее всплывали вот так на поверхность, оставалась одна-одинешенька и смотрела им вслед, и ей впору было заплакать, да только русалкам не дано слез, и от этого ей было еще горше.

- Ах, когда же мне будет пятнадцать лет! - говорила она. - Я знаю, что очень полюблю тот мир и людей, которые там живут!

Наконец и ей исполнилось пятнадцать лет.

- Ну вот, вырастили и тебя! - сказала бабушка, вдовствующая королева. - Поди-ка сюда, я украшу тебя, как остальных сестер!

И она надела русалочке на голову венок из белых лилий, только каждый лепесток был половинкой жемчужины, а потом нацепила ей на хвост восемь устриц в знак ее высокого сана.

- Да это больно! - сказала русалочка.

- Чтоб быть красивой, можно и потерпеть! - сказала бабушка.

Ах, как охотно скинула бы русалочка все это великолепие и тяжелый венок! Красные цветы с ее грядки пошли бы ей куда больше, но ничего не поделаешь.

- Прощайте! - сказала она и легко и плавно, словно пузырек воздуха, поднялась на поверхность.

Когда она подняла голову над водой, солнце только что село, но облака еще отсвечивали розовым и золотым, а в бледно-красном небе уже зажглись ясные вечерние звезды; воздух был мягкий и свежий, море спокойно. Неподалеку стоял трехмачтовый корабль всего лишь с одним поднятым парусом - не было ни малейшего ветерка. Повсюду на снастях и реях сидели матросы. С палубы раздавалась музыка и пение, а когда совсем стемнело, корабль осветился сотнями разноцветных фонариков и в воздухе словно бы замелькали флаги всех наций. Русалочка подплыла прямо к окну каюты, и всякий раз, как ее приподымало волной, она могла заглянуть внутрь сквозь прозрачные стекла. Там было множество нарядно одетых людей, но красивее всех был молодой принц с большими черными глазами. Ему, наверное, было не больше шестнадцати лет. Праздновался его день рождения, оттого-то на корабле и шло такое веселье. Матросы плясали на палубе, а когда вышел туда молодой принц, в небо взмыли сотни ракет, и стало светло, как днем, так что русалочка совсем перепугалась и нырнула в воду, но. тут же опять высунула голову, и казалось, будто все звезды с неба падают к ней в море. Никогда еще не видала она такого фейерверка. Вертелись колесом огромные солнца, взлетали в синюю высь чудесные огненные рыбы, и все это отражалось в тихой, ясной воде. На самом корабле было так светло, что можно было различить каждый канат, а людей и подавно. Ах, как хорош был молодой принц! Он пожимал всем руки, улыбался и смеялся, а музыка все гремела и гремела в чудной ночи.

Уже поздно было, а русалочка все не могла глаз оторвать от корабля и от прекрасного принца. Погасли разноцветные фонарики, не взлетали больше ракеты, не гремели пушки, зато загудело и заворчало в глуби морской. Русалочка качалась на волнах и все заглядывала в каюту, а корабль стал набирать ход, один за другим распускались паруса, все выше вздымались волны, собирались тучи, вдали засверкали молнии.

Надвигалась буря, матросы принялись убирать паруса. Корабль, раскачиваясь, летел по разбушевавшемуся морю, волны вздымались огромными черными горами, норовя перекатиться через мачту, а корабль нырял, словно лебедь, между высоченными валами и вновь возносился на гребень громоздящейся волны. Русалочке все это казалось приятной прогулкой, но не матросам. Корабль стонал и трещал; вот подалась под ударами волн толстая обшивка бортов, волны захлестнули корабль, переломилась пополам, как тростинка, мачта, корабль лег на бок, и вода хлынула в трюм. Тут уж русалочка поняла, какая опасность угрожает людям, - ей и самой приходилось увертываться от бревен и обломков, носившихся по волнам. На минуту стало темно, хоть глаз выколи, но вот блеснула молния, и русалочка опять увидела людей на корабле. Каждый спасался, как мог. Она искала глазами принца и увидела, как он упал в воду, когда корабль развалился на части. Сперва она очень обрадовалась - ведь он попадет теперь к ней на дно, но тут же вспомнила, что люди не могут жить в воде и он приплывет во дворец ее отца только мертвым. Нет, нет, он не должен умереть! И она поплыла между бревнами и досками, совсем не думая о том, что они могут ее раздавить. Она то ныряла глубоко, то взлетала на волну и наконец доплыла до юного принца. Он почти уже совсем выбился из сил и плыть по бурному морю не мог. Руки и ноги отказывались ему служить, прекрасные глаза закрылись, и он утонул бы, не явись ему на помощь русалочка. Она приподняла над водой его голову и предоставила волнам нести их обоих куда угодно...

К утру буря стихла. От корабля не осталось и щепки. Опять засверкало над водой солнце и как будто вернуло краски щекам принца, но глаза его все еще были закрыты.

Русалочка откинула со лба принца волосы, поцеловала его в высокий красивый лоб, и ей показалось, что он похож на мраморного мальчика, который стоит у нее в саду. Она поцеловала его еще раз и пожелала, чтобы он остался жив.

Наконец она завидела сушу, высокие синие горы, на вершинах которых, точно стаи лебедей, белели снега. У самого берега зеленели чудесные леса, а перед ними стояла не то церковь, не то монастырь - она не могла сказать точно, знала только, что это было здание. В саду росли апельсинные и лимонные деревья, а у самых ворот высокие пальмы. Море вдавалось здесь в берег небольшим заливом, тихим, но очень глубоким, с утесом, у которого море намыло мелкий белый песок. Сюда-то и приплыла русалочка с принцем и положила его на песок так, чтобы голова его была повыше на солнце.

Тут в высоком белом здании зазвонили колокола, и в сад высыпала целая толпа молодых девушек. Русалочка отплыла подальше за высокие камни, торчавшие из воды, покрыла свои волосы и грудь морскою пеной, так что теперь никто не различил бы ее лица, и стала ждать, не придет ли кто на помощь бедному принцу.

Вскоре к утесу подошла молодая девушка и поначалу очень испугалась, но тут же собралась с духом и позвала других людей, и русалочка увидела, что принц ожил и улыбнулся всем, кто был возле него. А ей он не улыбнулся, он даже не знал, что она спасла ему жизнь. Грустно стало русалочке, и, когда принца увели в большое здание, она печально нырнула в воду и уплыла домой.

Теперь она стала еще тише, еще задумчивее, чем прежде. Сестры спрашивали ее, что она видела в первый раз на поверхности моря, но она ничего им не рассказала.

Часто по утрам и вечерам приплывала она к тому месту, где оставила принца. Она видела, как созревали в саду плоды, как их потом собирали, видела, как стаял снег на высоких горах, но принца так больше и не видала и возвращалась домой каждый раз все печальнее. Единственной отрадой было для нее сидеть в своем садике, обвив руками красивую мраморную статую, похожую на принца, но за своими цветами она больше не ухаживала. Они одичали и разрослись по дорожкам, переплелись стеблями и листьями с ветвями деревьев, и в садике стало совсем темно.

Наконец она не выдержала и рассказала обо всем одной из сестер. За ней узнали и остальные сестры, но больше никто, разве что еще две-три русалки да их самые близкие подруги. Одна из них тоже знала о принце, видела празднество на корабле и даже знала, откуда принц родом и где его королевство.

- Поплыли вместе, сестрица! - сказали русалочке сестры и, обнявшись, поднялись на поверхность моря близ того места, где стоял дворец принца.

Дворец был из светло-желтого блестящего камня, с большими мраморными лестницам; одна из них спускалась прямо к морю. Великолепные позолоченные купола высились над крышей, а между колоннами, окружавшими здание, стояли мраморные статуи, совсем как живые люди. Сквозь высокие зеркальные окна виднелись роскошные покои; всюду висели дорогие шелковые занавеси, были разостланы ковры, а стены украшали большие картины. Загляденье, да и только! Посреди самой большой залы журчал фонтан; струи воды били высоко-высоко под стеклянный купол потолка, через который воду и диковинные растения, росшие по краям бассейна, озаряло солнце.

Теперь русалочка знала, где живет принц, и стала приплывать ко дворцу почти каждый вечер или каждую ночь. Ни одна из сестер не осмеливалась подплывать к земле так близко, ну а она заплывала даже в узкий канал, который проходил как раз под мраморным балконом, бросавшим на воду длинную тень. Тут она останавливалась и подолгу смотрела на юного принца, а он-то думал, что гуляет при свете месяца один-одинешенек.

Много раз видела она, как он катался с музыкантами на своей нарядной лодке, украшенной развевающимися флагами. Русалочка выглядывала из зеленого тростника, и если люди иногда замечали, как полощется по ветру ее длинная серебристо-белая вуаль, им казалось, что это плещет крыльями лебедь.

Много раз слышала она, как говорили о принце рыбаки, ловившие по ночам с факелом рыбу, они рассказывали о нем много хорошего, и русалочка радовалась, что спасла ему жизнь, когда его, полумертвого, носило по волнам; она вспоминала, как его голова покоилась на ее груди и как нежно поцеловала она его тогда. А он-то ничего не знал о ней, она ему и присниться не могла!

Все больше и больше начинала русалочка любить людей, все сильнее тянуло ее к ним; их земной мир казался ей куда больше, чем ее подводный; они могли ведь переплывать на своих кораблях море, взбираться на высокие горы выше облаков, а их страны с лесами и полями раскинулись так широко, что и глазом не охватишь! Очень хотелось русалочке побольше узнать о людях, о их жизни, но сестры не могли ответить на все ее вопросы, и она обращалась к бабушке: старуха хорошо знала “высший свет”, как она справедливо называла землю, лежавшую над морем.

- Если люди не тонут, - спрашивала русалочка, - тогда они живут вечно, не умирают, как мы?

- Ну что ты! - отвечала старуха. - Они тоже умирают, их век даже короче нашего. Мы живем триста лет; только когда мы перестаем быть, нас не хоронят, у нас даже нет могил, мы просто превращаемся в морскую пену.

- Я бы отдала все свои сотни лет за один день человеческой жизни,-проговорила русалочка.

- Вздор! Нечего и думать об этом! - сказала старуха. - Нам тут живется куда лучше, чем людям на земле!

- Значит, и я умру, стану морской пеной, не буду больше слышать музыку волн, не увижу ни чудесных цветов, ни красного солнца! Неужели я никак не могу пожить среди людей?

- Можешь, - сказала бабушка, - пусть только кто-нибудь из людей полюбит тебя так, что ты станешь ему дороже отца и матери, пусть отдастся он тебе всем своим сердцем и всеми помыслами, сделает тебя своей женой и поклянется в вечной верности. Но этому не бывать никогда! Ведь то, что у нас считается красивым - твой рыбий хвост, например, - люди находят безобразным. Они ничего не смыслят в красоте; по их мнению, чтобы быть красивым, надо непременно иметь две неуклюжие подпорки, или ноги, как они их называют.

Русалочка глубоко вздохнула и печально посмотрела на свой рыбий хвост.

- Будем жить - не тужить! - сказала старуха. - Повеселимся вволю, триста лет - срок немалый... Сегодня вечером у нас во дворце бал!